T.S. Tirumurti

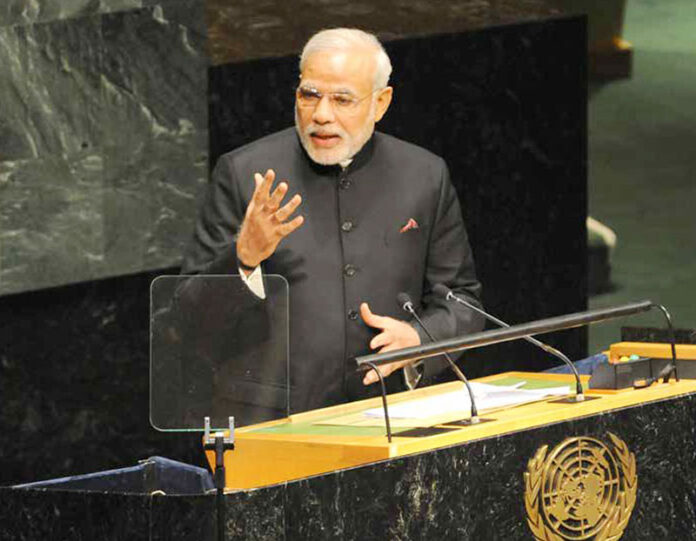

Reformed multilateralism was first articulated by Prime Minister Modi at the Leaders Retreat in BRICS Summit 2018 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The idea found ready resonance with the then BRICS Chair, President Cyril Ramaphosa, and with Brazil. But the other two BRICS were more circumspect on the concept of reformed multilateralism.

As Indian External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar said recently, “As the international order evolves, this desire to selectively retain elements of the 1945 situation while transforming others — and we see that in the UN as well — complicates world politics.” China, and to a much lesser extent Russia, were willing to go for reform of World War II institutions only as long as it suited their objectives. Their objectives did not go as far as embracing the desire of the three IBSA countries (India, Brazil and South Africa) to become permanent members of the UN Security Council.

The UN Security Council stands diminished for various reasons most of which can be traced back to its unrepresentative and anachronistic nature. For example, nearly 70 percent of the agenda of the Council concerns Africa. But without permanent African representation, what credibility does the Council have if former colonial masters (however well-intentioned they may be) decide what is good for Africa? As Dr. Jaishankar mentioned in the UN General Assembly “It is also perceived as deeply unfair, denying entire continents and regions a voice in a forum that deliberates their future.”

Reform has become even more urgent since the Security Council is now taking an expansive view of what constitutes international peace and security by including purely socio-economic and environmental issues under this rubric as well so that the P-5 can become arbiters of others’ destiny without representation. This is clearly not desirable. The Council needs to be reformed to reflect contemporary realities by bringing in more permanent members from developing countries.

Inability of multilateral institutions to deal effectively with geopolitical and other socio-economic and financial challenges, which includes lack of reforms in IMF, World Bank and WTO, has spawned several plurilateral groups seeking to address some specific areas or regions of interest. For them, it is a way to negotiate new rules and regulations and influence the larger context of multilateralism. This is a direct fall out of the burgeoning variety of challenges and the inability of current multilateral governance structures to tackle them. If China and Chinese-led multilateral institutions have started stepping into the multilateral financial and economic space, it is because of the procrastination of the developed world to ensure a more inclusive decision-making in IMF and multilateral banks.

However, multilateralism goes beyond the UN and economic and financial institutions. In the Ukraine conflict, we have seen the weaponization of almost everything and that too, unilaterally. In other regions, we have also witnessed how unilateral sanctions affect large parts of the developing world. That is because of the confidence that those undertaking such unilateral ‘weaponization’ will never be called to account. Their actions in Ukraine have been taken in disregard of the welfare and interests of the developing world whether oil, food, fertilizers or finance. We need to induce greater accountability for such actions. Consequently, we need a reformed and inclusive multilateral architecture to prevent this ‘weaponization’ of almost everything.

That brings us to G20. Can G20 become the fulcrum around which the multilateral reform process revolves? In some ways it already has, by its very existence. G20 is now probably the most representative of the various plurilateral groups. All regions find representation, though the EU is over-represented, Africa is under-represented and there is no small island state in sight. Its creation in the aftermath of the economic crisis of 1997-98, and its decisions including during the 2008 economic crisis and during COVID have had their desired socio-economic and environmental impact. Since it works by consensus, the G20 countries are forced to compromise to arrive at an acceptable decision.

In effect, everyone has a veto and no one has a veto. Consensus decisions make for prompt implementation even if these decisions do not necessarily have a binding force. Therefore, process-wise, G20 has all the ingredients for replication with proper tweaking of the numbers and the membership list. But substance-wise? There can be little doubt that G20 remains the best forum to pursue reform of financial and economic multilateral institutions and banks and effect changes in the outdated 1945 architecture. For example, the drying up of funds, inter alia, for tackling Covid fall-out, for strengthening climate action and for pursuing SDGs, remains a serious concern.

Donors understandably do not want others to decide on how their money should be deployed, especially when there are burgeoning and conflicting demands from conflicts, new and old, and huge humanitarian requirements especially after Covid. We have seen how the COVAX Facility failed when the West decided to hoard vaccines for themselves and did not put in any funding into COVAX, thereby depriving the Global South of the much-needed life-saving vaccines. G20 provides just the right mix and balance to deal with these issues in a serious and inclusive manner, initiate action to reform and address these gaps in governance.

The Ukraine conflict has also changed the way some have started seeing G20. Just as work was stopped by the EU, the US and the West in the UN and the UN Security Council was rendered impotent by the Russian veto, so have the outcomes from the various G20 work streams been stymied under the Indonesian presidency. G7 countries have so far not let consensus decisions be reached in any work stream barring one. Rest are all Chair’s summaries, which have far less binding force.

Politicization of G20 is now in full public glare and G20 has also been weaponized! We now see G20 taking hesitant steps into political issues and the door has been pried open.Therefore, when it comes to how much and how far G20 can go to bring about reformed multilateralism, the jury is still out. But the fact that G20 has become a more representative and inclusive governance structure is undeniable. And the fact that all major powers have taken the G20 seriously augurs well for the future. The center of gravity has shifted towards G20. Maybe the seeds of UN Security Council’s expansion have unwittingly been sown.

In a happy coincidence, we are now witnessing four consecutive years of G20 presidency by developing countries — Indonesia, India, Brazil and South Africa, which gives the Global South the possibility of leaving their imprint on the themes and deliberations in G20. The least these presidencies can do is to address the issues of the developing world in a more direct and positive way.

India’s presidency, therefore, gives a unique opportunity to channelize the demands and interests of the Global South into G20 deliberations. It gives an opportunity to handle an almost universal fall-out from the Ukraine conflict. And India’s priorities for G20 reflects the keen interest we have in reformed multilateralism. One of our five priorities is ‘Need for reformed 21st century institutions.’ No doubt that this will be a peg to hang some important reform initiatives for the developing world.

Showcasing some of India’s success stories for public good, like our digital and green initiatives, will be a game changer. Further, India has invited nine guest countries to bring greater balance in the participation. Overall, India is particularly well poised to lead the G20 with an agenda for reform, greener and gender sensitive development, inclusivity, growth, change and innovation.

[T.S. Tirumurti was India’s Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations in New York (2020-2022) and President of the UN Security Council for August 2021. He chaired the Counter- Terrorism Committee and the Taliban Sanctions Committee of the UN Security Council. He served as Secretary (Economic Relations) in the Ministry of External Affairs (2018-2020). His distinguished diplomatic career includes stints as Indian High Commissioner to Malaysia and the first Representative of India to the Palestinian Authority in Gaza.]

[T.S. Tirumurti was India’s Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations in New York (2020-2022) and President of the UN Security Council for August 2021. He chaired the Counter- Terrorism Committee and the Taliban Sanctions Committee of the UN Security Council. He served as Secretary (Economic Relations) in the Ministry of External Affairs (2018-2020). His distinguished diplomatic career includes stints as Indian High Commissioner to Malaysia and the first Representative of India to the Palestinian Authority in Gaza.]