THE TIMES KUWAIT REPORT

The prevailing bonhomie in parliament between the executive and legislative, an improving economic situation from higher global oil prices, and a COVID-19 crisis that appears to be under control, has allowed the government to sit back and enjoy a spell of well-earned respite. But should it be relaxing during what could be a brief balmy period in the political and economic climate? Though the answer to this from a long-suffering citizenry would be a resounding ‘no’, the government appears to be tone deaf to this public entreaty.

Rather than relaxing during ‘better times’, the government should be leveraging the narrow window of opportunity provided by the ongoing camaraderie in parliament to push through much-needed economic, financial and social reforms. As we have long maintained, economic reforms are best implemented when the economy is on an upswing, as it is now.

But based on historical precedent it is obvious that government exhortations for reforms and its stress on austerity are usually confined to periods when the economy is in a downward spiral. The moment oil prices begin heading north, the authorities tend to forget the belt-tightening measures and reform packages that were deemed essential, and plans and policies in this regard are either shelved or pushed to the back burner. This is once again what appears to be happening under the present scenario of higher oil prices.

The window of opportunity opened up by the decision last November, of His Highness the Amir Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al Sabah to grant a pardon to several political dissidents, and to reduce the jail-sentences of others, appears to be still ajar. An Amiri amnesty for dissident compatriots living in self-imposed exile abroad, which had been the unarticulated but key demand of opposition lawmakers who were locked in a standoff with the government through much of 2021, has resulted in a cooling down of political tensions in parliament. This period of seeming detente should be seized by the government to push through its reform agendas. But the question is, will it?

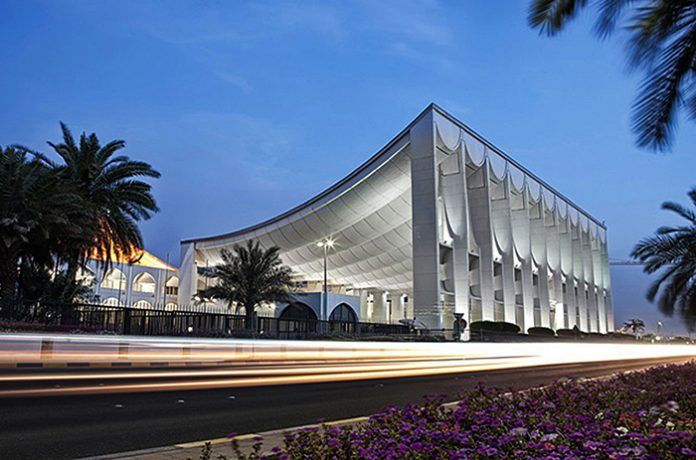

Parliamentary congeniality generated by the amnesty has been evident since the start of a new session of the National Assembly in January. The oath-taking ceremony of the new cabinet, headed once again by the veteran Prime Minister His Highness Sheikh Sabah Khaled Al-Hamad Al-Sabah, went ahead without a hitch. And, quite uncharacteristically, the opposition did not bat an eyelid when the premier announced his new cabinet line up, which usually serves as a starting point for recriminations against the government. Also, since the start of the new session, there have been no attempts by the opposition to thwart parliamentary proceedings or heckle government ministers.

In this regard it bears pointing out that an astute move by the prime minister to co-opt some members of the opposition in his newly formed cabinet has led to an apparent shift in the balance of power on the National Assembly floor. This slight swing in favor of the executive in parliament was evident in the 23 to18 vote in favor of the defense minister during the no confidence motion brought against him by the opposition in January. The pro-government sway has also been evident in several other smaller political skirmishes in the National Assembly since then.

However, political analysts believe any attempt by the executive to test this new parliamentary balance aggressively could have unforeseen consequences. The government for its part is also, quite understandably, not too keen to agitate the current status quo and unsettle the existing precarious balance. As such, economic, political and social reforms that are deemed urgent, but are contentious in parliament, are unlikely to be pushed through any time soon.

Moreover, as is the norm when the economy begins to look up, the government has little interest, and even less inclination, in introducing painful economic and financial reforms that could rattle the opposition. Local economic analysts and venerable international organizations, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, have repeatedly stated that Kuwait needs to urgently introduce key economic reforms in order to ensure the long-term stability and sustainability of the country and its economy.

Despite being aware of the urgency of reforms, the prevailing higher oil price scenario has allowed the government enough leeway to shelve reforms, at least for the time being. Rather than confront the opposition in parliament and push through its reform agendas using the thin majority that it ostensibly enjoys in parliament, the government has chosen the path of least resistance. The cabinet in its infinite wisdom has apparently decided that it is better to appease than to antagonize the opposition and risk ruffling the existing detente in parliament.

If any corroboration of the government’s appeasement policy was needed it was provided most recently last week by the decision by the authorities to cancel a planned women’s yoga event without assigning any valid reason. Media reports attribute this abrupt decision by the authorities to the insistence of opposition MP Hamdan Al-Azmi, who called for its cancellation terming the event as an alien practice extraneous and dangerous to the values, customs and traditions of a conservative Kuwait society.

Political blocs in parliament, including the National Democratic Alliance and the Kuwait Progressive Movement, have denounced “the government weakness in caving-in to parliamentary pressures that hold the state hostage to its strict religious patterns. The coalition blamed the premier for capitulating to the demands and blackmailing tactics by representatives of political Islam, in order to protect his own chair. They called for confronting this reality that is being imposed on the state, society and individuals in Kuwait. As such incidents get repeated, it is quite possible that the government could very well end up appeasing parliamentarians and displeasing the public.

On the economic front, with oil revenue as its main source of income, Kuwait is overwhelmingly dependent on global oil prices remaining in the high bandwidth. Oil accounts for nearly half of Kuwait’s GDP, around 95 percent of exports, and approximately 90 percent of government revenue. Any precipitous fall in international price of oil — as happened in mid-2014 and through much of 2020 due to global COVID-19 pandemic — has a disproportionate negative impact on Kuwait’s economy and on business activity in the country.

But with oil prices on an upward trajectory, the government seems unwilling to heed the economic urges of experts, forgetting the repercussions that followed the low oil price scenario in 2014 and 2020, and instead prefers to bask in the warmth arising from the current high oil prices. Higher oil prices that translate to higher income for Kuwait and happier times for the government was also discernible in the draft budget for fiscal year 2022-2023 that begins on 1 April 2022 and ends on 31 March, 2023.

The draft budget was presented on 24 January by the ministry of finance to the Cabinet for approval, and subsequent submission to the National Assembly for ratification. Presenting the draft budget to his cabinet colleagues, the Minister of Finance and Minister of State for Economic Affairs and Investments, Abdulwahab Al-Rushaid said that expenditures in the budget had been trimmed in line with directions from the cabinet.

The budget shows that the ceiling of spending has now been set at KD21.9 billion, with projected revenues estimated at KD18.8 billion, of which the forecast from oil proceeds were in the range of KD16.7 billion, representing 88.8 percent of projected revenues, up from the 83.4 percent in the current budget. Non-oil income has been estimated at KD2.1 billion, an increase of 15.3 percent from the ongoing budget. The draft budget envisages an overall deficit of KD3.1 billion, which is a steep drop of 74.5 percent from deficit in the previous year.

Capital spending in the budget has been capped at KD2.9 billion. More importantly, the draft shows that over KD16.3 billion or 74.5 percent of total government expenditure would be allocated to civil service wages and public subsidies. The budget is based on an assumed oil price of $65 per barrel and a break-even price of $75 per barrel. Relative to prevailing international oil prices, the low base oil price set in the budget could very well lead to the government actually realizing a surplus in its budget at the end of fiscal year 2022-2023.

A surplus budget in the coming fiscal year, the first one since 2016, should be welcome news to the government, which has since 2017 been struggling to pass a contentious debt law through parliament. Over the years, multiple revisions made to the public debt bill in attempts to mollify lawmakers, have failed to convince parliament on the need to pass the bill. The inability to raise money on the international debt market through the debt law has made the financing of deficit budgets in previous years an onerous task for the then incumbent finance minister.

The potential surplus in the upcoming budget is dependent on oil prices remaining in the higher price bracket over the coming period, and averaging above Kuwait’s break even point of $75 per barrel. In what could be a propitious sign, oil analysts predict that prices, which have shown an upward trajectory through much of 2021, are expected to maintain this trend in 2022. Oil has clawed its way back from the lows it experienced during the height of the pandemic in 2020. The climb was supported by a surge in global demand for oil due to a revival in global economic growth following a fall in COVID-19 infections, increase in vaccination rates and a relaxing of pandemic-related restrictions in many countries during 2021.

However, these rosy predictions and the potential of a surplus budget in 2022-2023 have not dented the less than optimistic view held by local and international economists familiar with Kuwait’s economy and its deep-rooted undercurrents of structural imbalances. Last year, the former Finance Minister Khalifa Hamada had warned that Kuwait’s cumulative budget deficit in the five years ending 31 March 2025 could top KD55.4 billion. He noted that total expenses during that period are projected at KD114 billion, with 71 percent, or KD81 billion, allocated to salaries and subsidies, which is untenable and unsustainable.

The former minister stressed that issuing bonds through a public debt law and withdrawing cash from the country’s sovereign wealth fund are not solutions to reform and are merely temporary measures to finance the deficit. He added that the country needed to address its liquidity problem as soon as possible, and urgently implement necessary reforms, cut spending and boost non-oil income.

Adding its weight to the former finance minister’s warning, global rating agency Fitch Ratings downgraded Kuwait’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘AA-’, from ‘AA’, with the outlook labeled ‘Stable’ on 27 January.

In a statement the global agency said Kuwait’s downgrade reflected ongoing political constraints on decision-making that hinder addressing structural challenges related to heavy oil dependence, a generous welfare state and a large public sector. The statement noted that there has been a lack of meaningful underlying fiscal adjustment to recent oil-price shocks and the outlook for reforms remains weak, despite some positive political developments as part of a ‘national dialogue’. Fitch added that while it assumed that a debt law could be passed through parliament in 2022, the fact that this bill has been under discussion since 2017, reflects the slow decision-making process in Kuwait.

Oil analysts at Fitch Ratings expect annual Brent crude prices to average $70 per barrel in 2022 and $60 per barrel in 2023. Meanwhile, Kuwait’s average oil production is expected to increase to 2.7 million barrels per day in fiscal year 2022, and to 2.8 million barrels per day in fiscal 2023, from the current level of 2.5 million barrels per day, following revision in annual production quotas agreed upon by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its non-OPEC allies.

Fitch bases its calculation on an estimate that every $10 per barrel change in oil prices impacts Kuwait’s budget by around 5.5 percent of GDP, all things else being equal. Also, that a change of 100,000 barrels a day in production affects the budget by about 1.7 percent of GDP.

To the country’s credit, and despite the absence of debt law to facilitate borrowing and shore-up its budget deficits since 2016, Kuwait has steadfastly managed to fulfill its local needs and meet its international debt obligations. To fund its deficits and meet its gross financing needs, the government has relied on assets in its General Reserve Fund (GRF), which serves as the state treasury. However, steady outflows in the face of repeated budget deficits had all but depleted the GRF by the end of 2020. Though the government has not disclosed the GRF’s current level of liquid assets it is assumed that it will be sufficient to cover Kuwait’s $3.5 billion eurobond that matures in March 2022.

No matter what the prevailing political relations are, or how high oil prices climb, the government needs to wake up and urgently resolve the country’s long standing structural imbalances and introduce necessary reforms. Only then can the economy realize its full potential and remain stable and sustainable going forward.