In the 1930s and 40s, it was to the erstwhile British colonies of Singapore and Malaysia that the first waves of professionally-qualified migrants from the Indian state of Kerala set out. The newly-independent India of the fifties and the sixties witnessed other Indian-educated migrants leaving her shores in the pursuit of better career opportunities in the West.

During the accelerated decolonization process in the Middle East in the sixties and countries emerging as independent states, several Middle Eastern nations, including Kuwait, sought to consolidate and independently control their very considerable oil wealth. It became imperative for these countries to hire both skilled and unskilled workers in order to extract, exploit, refine and move these resources and power their economies.

Generation of distilled water and electricity were essential to the development of basic infrastructure in these countries and for the production of their new-found oil wealth. Kuwait, with no natural freshwater sources of its own, had earlier relied on transporting freshwater from Basra in Iraq via dhow or even on the backs of donkeys. Independence and abundant oil revenues enabled Kuwait to set up its own desalination plants to meet the country’s industrial and domestic requirements.

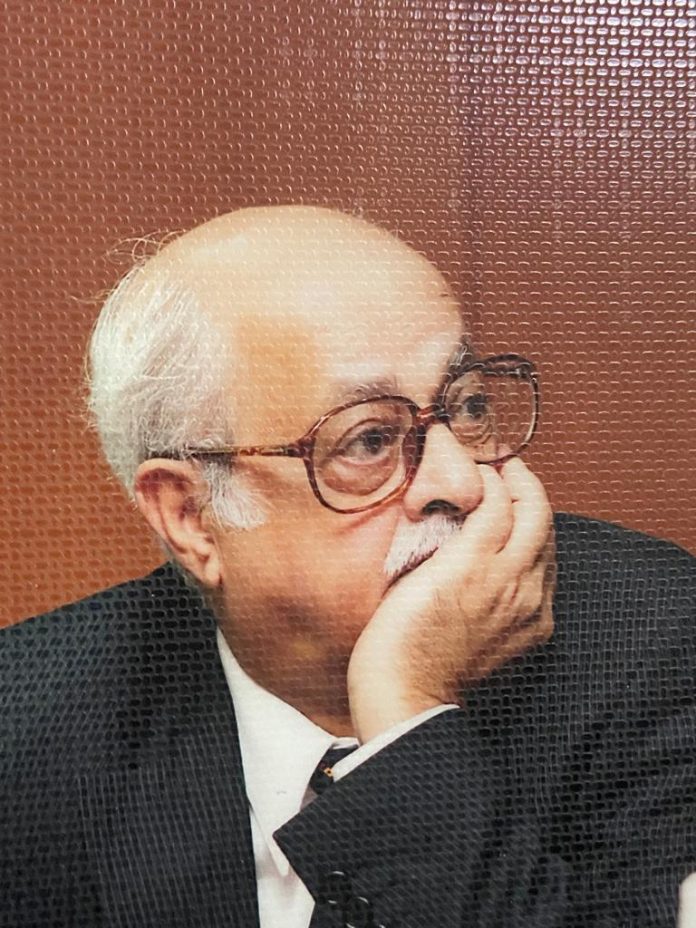

Needing skilled workers for these massive electricity and water projects, Kuwait’s Ministry of Electricity and Water (MEW) advertised for these vacancies in leading newspapers in India. In 1962, John Mathew, a chemical engineer then employed with Fertilizers And Chemicals Travancore (FACT) in Kerala was hired by MEW.

Three years later, he was hired by the Petrochemical Industries Company, which was then known as Kuwait Chemical Fertilizer. As part of its aggressive expansion plans, the company sent Mr. Mathew to the US, and to the Netherlands to attend training programs for a year and a half. On his return, he began working with top management in the organization.

An expat’s life is a kind of self-imposed exile. Out of necessity, he uproots himself from his native land, abandons his former life and everything he knows and holds dear to find his way in strange new lands, with their strange customs and alien socio-economic dynamics.Though nostalgia plagues him and memories remind him of all that he had to sacrifice when he set out on his journey. He often finds himself unable to surmount the odds and adversities stemming from being subjected to this process, but finds in himself the strength to soldier on.

For some expats, Gulf countries are often a transit point to seeking fortunes in other places, including the US, Europe and elsewhere. Even though he was inundated with lucrative offers from multinational corporations in Western nations, promising even higher advancement up the corporate ladder, Mr. Mathew realized that Kuwait was where he needed to be and chose to remain here.

It has been 60 years since Mr. Mathew first set foot in Kuwait, as he prepares to retire and return to his native land, we asked him what made him decide to return home. He quips, “… my social life has died out, most of my friends have either moved back home or are no longer with us. I can literally count the number of friends I have here, while back home, I have too many friends and relatives to count.”

As a capital investor and board member in three companies in Kuwait, Mr.Mathew holds an Investor Status No 19 visa, which enables him and his family to continue living in Kuwait as expatriates for as long as they wish. In 1981, with his entrepreneurial spirit taking charge and spurring him to strike out on his own, he started his own company, providing employment to more than 7,000 people in the years since.

The late K. M. Mani, a political strongman from Kerala, once humorously remarked that Keralites have a penchant for creating political factions within factions because they all want to lead. Though he was an active member of the Students’ Federation of India when he was at the university and later a member of the Communist Party’s trade union organization during his stint at FACT, Mr. Mathew was neither actively involved with any of the multitude of Keralite associations in Kuwait, nor did he seek to lead any of them.

He is happy that over the years he has been able to help the less privileged and downtrodden members of society, He is especially proud of serving as a transportation coordinator in the volunteer committee, formed by Indian community leader the late M. Mathews, with the singular goal of safely repatriating over 125,000 Indians who found themselves turned into refugees overnight when Kuwait was invaded by Iraq in 1990.

Hiring Iraqi buses with donations from passengers to ferry more than 100,000 Indians by road to the Jordanian border without the help of a single government agency was a task fraught with risks and challenges. As John Mathew recounts these events, one can see the pride he feels in having participated in this humanitarian endeavor which is now regarded as the largest civilian evacuation in history.

He recalls that, in those days of uncertainty, a greater challenge was the protection and repatriation of domestic helpers who were abandoned when their sponsors fled their homes in the wake of Iraqi aggression. John and his colleagues in the volunteer committee were the last ones to board the last bus out of Kuwait, after having ensured that every Indian who wished to go back home, including women domestic helpers, were safely and securely on their way to the Jordanian border.

When the Non-Resident Keralites Affairs (NORKA) was formed by the Government of Kerala, the state government appointed Mr. Mathew as NORKA’s official Kuwait representative. At the time, he was actively engaged in ensuring that the petitions of those who were unable to apply at the UN Compensation Commission for financial reparations following the Iraqi occupation were collected and forwarded to NORKA. In this regard, he collaborated with the Indian coordinator at the UN Commission in Geneva, Swashpawan Singh (former Indian Ambassador to Kuwait), and saw to it that those applying for compensation even during the final rounds were given their dues.

When asked about his opinion on the matter of the Kuwait government’s policy of not providing residence permits to non-graduates over the age of 60, Mr. Mathew, now 84, said: “The age of 55 to 75 years is that phase in a person’s life when he can function as a contributing member of society using the vast experience and knowledge that he has accumulated over the years. Any society would do well to utilize their experience. It could only be beneficial to the nation and society.” He goes on to add, “… even if I am back home, I will continue to be involved with the day-to-day activities of my business. I am a workaholic. I believe in working hard. Work hard and enjoy the fruits of your labor. Enjoy the luxuries you can afford. Live your life happily and harm no one, is my motto.”

Among the books penned by Mr. Mathew is, ‘A Saga of an Expatriate’, an English semi-autobiographical novel set against the backdrop of the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait. He has also authored three other books in Malayalam. Below are a few of the questions posed towards the end of our meeting with Mr. Mathew:

Q: What is your best memory of Kuwait?

A: Arriving in Kuwait right after its liberation.

Q: What advice would you like to give those who are new to Kuwait?

A: Shortcuts to success often entail bad handiwork.

Q: How would you describe the Indian diaspora in Kuwait?

A: Successful, hardworking patriots.

John Mathew has three daughters, all engineering post-graduates, married and settled in the USA and England. His wife Remani Elizabeth John Mathew is a painter and a homemaker.

By Thomas Mathew Kadavil

Special to The Times Kuwait