Mai Al-Nakib was born and raised in Kuwait, although the first six years of her life were spent mainly in the United States. She studied English literature at university and is currently an associate professor of English and comparative literature at Kuwait University. For some time, her writing life centred around academic writing—journal articles, conference papers, and the like.

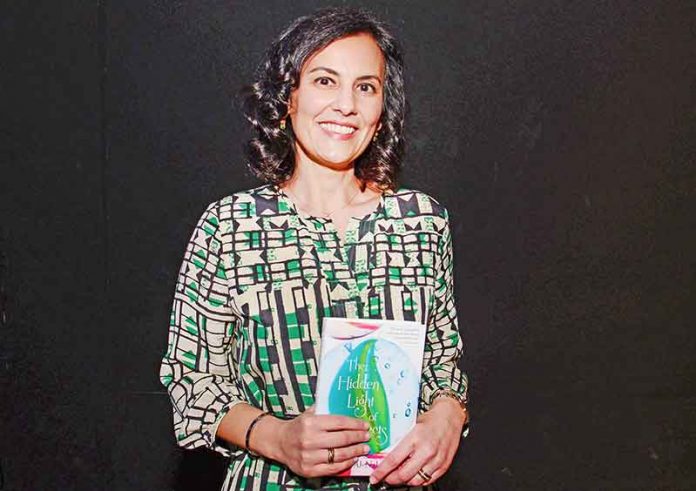

It wasn’t until she started teaching at Kuwait University that she felt the need to turn to a different form of writing, namely fiction. The Hidden Light of Objects is a collection of loosely connected short stories set mainly in the Middle East, which deal with loss and memory, war and love, and the strange longing objects can unexpectedly trigger. The Times had the pleasure of meeting with this newly published author to discuss her literary path.

When did you first consider yourself a writer?

Even as a kid, I thought of myself as a writer. Carrying around notebooks and scribbling in them felt like an indispensable part of who I was, who I considered myself to be. In graduate school, however, I began to think of myself more as an academic than a writer, though, of course, writing is one of the main occupations of academics. Happily, writing this collection has allowed me to rediscover my earlier sense of myself as a writer.

What does your book represent about the Middle East?

The book expresses certain experiences, sensations, or perceptions linked to the Middle East in a variety of ways, but these cannot be said to be representative. In fact, I’m sure many in the region will find some of the characters, settings, or events unfamiliar because the stories might not narrate or reflect their particular experiences. If anything, the collection conveys a sense of the Middle East as heterogeneous, far too rich and complex to be represented in any one text.

How does your book explore the culture and society of the Middle East?

In very intimate and singular ways. The Hidden Light of Objects conveys experiences of life in the Middle East not often depicted in the media, neither in the West nor in the Middle East itself. I never consciously set out to explore the culture or society of the Middle East because, first, my writing tends toward particularity—individual lives rather than broader contexts. Having said that, the concerns of particular characters always connect to their wider social context and that inevitably comes through in the stories.

Is there a message in your collection of short stories that you want readers to grasp?

I would never presume to impose any single message on readers since part of the pleasure of reading is to connect with texts in unique ways. Once a book is published and it’s out in the world, it belongs to its readers. I don’t have much of a say in what they do or do not grasp, and that’s as it should be.

Why did you decide to write about the Middle East in fiction?

As an academic, my main area of focus is Middle East cultural politics. When I turned to fiction, my first inclination was to write about the context I was most familiar with. A few of the stories in the collection are set outside the Middle East, but even those are related to the region in some way. Fiction makes it possible to approach issues I’m concerned with as an academic in ways I find tremendously appealing, in ways that are, perhaps, more flexible and layered. As a young reader, fiction opened up worlds for me, made it possible to connect with places and experiences I never would have otherwise. This is the special magic of fiction and it’s why I turned to it as a writer.

These stories are not autobiographical though, of course, elements of my life and my experiences do find their way into my writing. Because a number of the characters in the stories are female with a similar background to my own and because many of the stories are set in Kuwait, it might be easy to conclude that these stories are autobiographical. But that would be a mistake. These stories are fiction and so none of the characters represent me, even if certain aspects of the characters happen to express traces of my personal history.

How did you decide on the theme of the book?

Each of the stories in the collection can stand on its own, so I wouldn’t say there is any one theme holding them together. And yet, the stories are loosely connected. Not specifically by theme but, rather, by tone, language, characters, first-person vignettes, and—obvious from the title—a series of objects. The trope of objects is, above all, what holds the stories together.

How has the book been received by Kuwaiti readers?

I’m not aware of any reviews of the book in Kuwait yet, but individual readers have been very kind in their personal comments to me. At the various readings I’ve done this April—from the book launch at the Contemporary Art Platform to readings at the American University of Kuwait, Sultan Gallery, and Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya— turn-out has been great. It’s been very heartening.

What is your experience of Kuwait’s literary scene?

Not much, I’m afraid. I have great admiration for a number of Kuwaiti writers, but I’m not familiar with general tendencies. Because I write in English rather than Arabic, I’m not quite sure how, or if, I fit in.

What are the qualities of good writing?

I can’t generalize, but for me, good writing changes the way I see the world and challenges my expectations about form. When I read a great book, like Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude or Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled, I am not the same person at the end that I was in the beginning. That, to me, is the sign of great writing.

Why do you write?

I write because I have to, because I can’t imagine my life without it. Writing allows me to experiment with form, ideas, images, characters—in short, with life. It makes it possible for me to become something other than I am, to invent alternatives. It’s never easy. In fact, it’s always a struggle; some days, one sentence represents a good day of writing. But it’s a difficulty I would not trade for anything.

– Staff Report

Lecture and Reading at al-Maidan Cultural Center

On April 15, 2014, at 7 pm at al-Maidan Cultural Center, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya, Mai Al-Nakib, author of the short story collection, The Hidden Light of Objects (published by Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation), read a selection of excerpts from her new book. The lecture and reading were followed by a book signing.