Sundeep Bhutoria

Special to The Times Kuwait

“I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world and am free.”

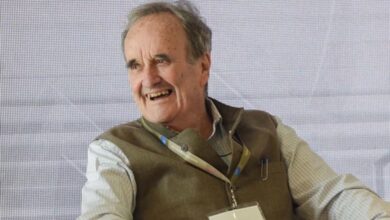

In the quiet sanctuary of Wendell Berry’s lines from “The Peace of Wild Things”, one finds solace. Today, those words return with a new weight — because the man who taught so many to seek that elusive peace in the wild is no more. Valmik Thapar, India’s most passionate advocate for the tiger and the soul of Ranthambore itself, who passed away.

In the quiet sanctuary of Wendell Berry’s lines from “The Peace of Wild Things”, one finds solace. Today, those words return with a new weight — because the man who taught so many to seek that elusive peace in the wild is no more. Valmik Thapar, India’s most passionate advocate for the tiger and the soul of Ranthambore itself, who passed away.

The news hit hard. For me, it’s not just the loss of a conservation icon — it’s the loss of a friend of Ranthambore – a place I hold closest to my heart – A fierce voice gone quiet. A presence impossible to replace.

Valmik wasn’t just India’s tiger man. He was Ranthambore. Not just in a symbolic way — he lived, breathed, and fought for it every single day. Through the awe he inspired in forest guards and guides, in villagers and visitors. Through the stories that clung to the park like mist — of Machli, Noor, Genghis— and of the man who gave us a reason to care.

Valmik started young, in the 1970s. Back then, Ranthambore was a fragile wilderness on the brink. What Valmik saw wasn’t just a threat — it was a possibility. He immersed himself in the jungle, studying tigers not just as a researcher, but as someone who understood their soul. He watched, he listened, , and he wrote it all down — articles, books, and documentaries that brought India’s tigers into living rooms and policy rooms alike.

Over a span of four decades, he authored a score of books on wildlife and conservation, including Tiger: The Ultimate Guide and Tiger Fire — the latter an anthology of India’s long and layered relationship with the big cat. He presented and co-produced several acclaimed documentaries for the BBC and National Geographic, such as Land of the Tiger, which aired internationally and educated millions on India’s wildlife.

He was appointed to India’s National Wildlife Board and served on countless conservation committees. In 1987, he founded the Ranthambhore Foundation, an NGO that pioneered community-led conservation and integrated livelihood support with environmental protection — a model that has since been emulated across protected areas in India.

Thapar wasn’t just documenting wildlife — he was shaping the national conversation around it. His work bridged the gap between field science, policy, and public imagination in a way few had before him.

And Valmik didn’t stop there. He challenged the system. Took on poachers, confronted politicians, questioned bureaucrats. He wasn’t afraid to make enemies if it meant protecting the wild. His roar often echoed louder in Delhi’s corridors than in the jungle itself.

Valmik saw conservation not as a job or a science — but as a moral calling. A duty. “I sighted my first tiger at the age of nine in Corbett Park. At 23, it became my obsession as watching it in the magical setting of Ranthambore mesmerised me like nothing else… Since then, I have served the tiger and will do so till I die,” Valmik once told my friend Ina Puri during a rare interview. That devotion shaped everything he did.

When I began working on Ranthambore Diary: 9 Days, 9 Cubs, it was Valmik’s shadow that loomed large. His way of seeing — of telling stories that made the wild feel personal — shaped my own journey. The very fact that I could witness and write about nine cubs in nine days is a tribute to what he helped build: a park where tigers still thrive because someone had the vision to fight for them.

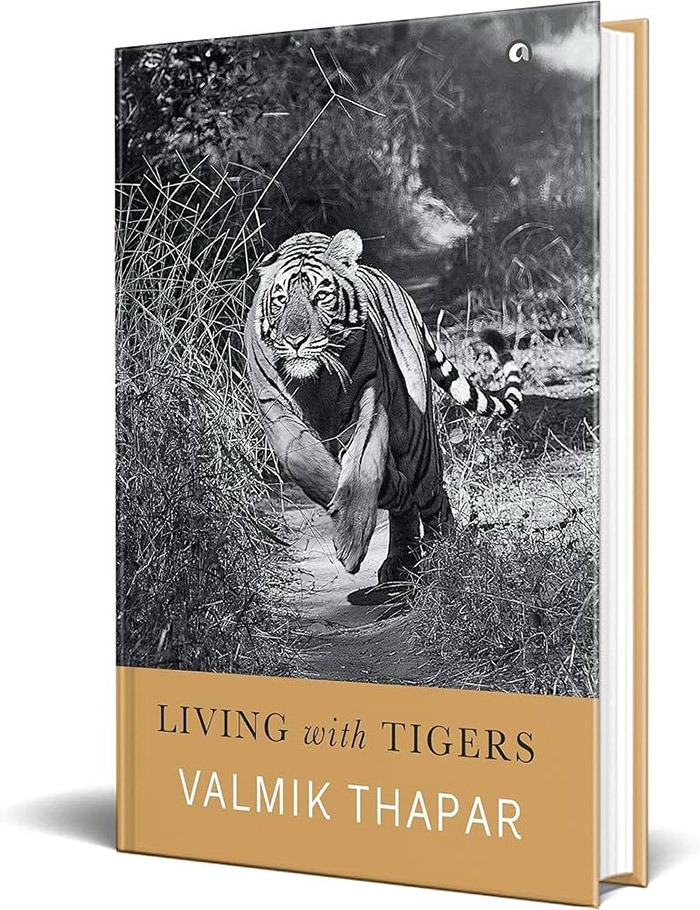

For his part, Valmik never stopped being astonished. In his book, Living with Tigers, he writes: “What I had seen was so intense that it was like being witness to atheatrical extravaganza.” That sense of wonder never left Valmik. Nor did his conviction that to conserve tigers was to conserve something deeper — a shared inheritance.

Ranthambore, to me, has never been just a park. It is a living narrative stitched together by decades of watchfulness, with Valmik as its most committed chronicler. Without his tireless advocacy, his fight against poachers and policy lapses, and his insistence on science and storytelling going hand in hand, the park would never have become what it is today.

But Valmik wasn’t just about Ranthambore. He advised prime ministers, served on key wildlife boards, and helped shape Project Tiger into what it became, both through his recommendations and his critiques. He wanted better protection, but also smarter tourism. He called out the glorified safari culture and pushed for regulation — always keeping the tiger at the centre.

I remember conversations where his eyes would light up while describing a tigress teaching her cubs to hunt. And others where his voice would drop, heavy with grief, recounting lost forests or failed policies. He was never detached. That was his greatest strength — and, sometimes, his burden.

Valmik’s passing leaves behind more than silence. It leaves a legacy — of truth-telling, of fierce love, of action. The best way to honour him isn’t through grand words. It’s by listening to the jungle and acting when it calls. I had no shortage of stories and anecdotes about him, thanks to another Tiger Man — Dharmendra Khandal — who kept his spirit alive in every tale he told.

The tiger has lost its most passionate guardian. But the trail Valmik blazed still runs deep. And we must follow.

(Mr Bhutoria has long been associated with Ranthambore and had recently released his coffee table book Ranthambore Diary: 9 Days, 9 Cubs , a best seller)