Memories of the Iraqi Occupation

By Claudia Farkas Al Rashoud

Special to the Times Kuwait

It has been 36 years since the Iraqi invasion and the memories of those terrifying events remain crystal clear; the sharp stab of fear in the pit of my stomach is still a deeply etched feeling.

I spent six weeks in Iraqi-occupied Kuwait, before being evacuated via Baghdad to the US with my two young sons. And before saying goodbye to my Kuwaiti husband, in-laws, and friends, I promised them, as soon as we reached safety, I would tell the world about what was happening in Kuwait. About the looting, the torture, and the killings, about the actions of the Kuwaiti Resistance, and what ordinary people were doing to survive in extraordinary circumstances, completely cut off from the outside world.

Following is my personal account of my experience during the Iraqi occupation, written from the notes in my daily diary, beginning with 2 August 1990. At dawn the sound of the telephone jerked me out of my sleep and into a waking nightmare. It was my sister-in-law, telling me Iraqi forces were invading Kuwait. “Can’t you hear the bombs? And there are tanks all over the city,” she said as I listened in disbelief.

Soon enough, the sounds of war reached our neighborhood. First the shelling was a series of dull thuds in the distance, but as it grew closer and louder the house shook. By 7am there was heavy fighting in our area, a fierce battle being fought by the impossibly outnumbered Kuwaiti soldiers at the army camp down the road.

An hour before, when we had switched on the radio, military marches were interrupted by an announcement from the Iraqis: “Congratulations to Kuwait and its new government. The Iraqi forces will remain here from a few days to a few weeks, until the situation is under control.”

By mid-morning, Iraqi soldiers were everywhere, shooting in the air and forcing motorists to abandon their vehicles and walk. They had taken over the Ministry of Information and other government offices, and turned the Sheraton Hotel into their headquarters. Thick clouds of black smoke were billowing from various parts of the city.

We decided it was safer to spend the night in the basement, so we took bedding downstairs and set up the video to keep our two little boys busy. Donald Duck cartoons blocked out the staccato crack of machine gun fire and the booming of the big guns. As night fell it grew quiet, but it was a silence fraught with fear. As my husband tuned into the radio, we were surprised to hear the voice of a lone unidentified Kuwaiti, broadcasting for the rapidly organised Resistance.

“Where are the Arab accords, the Gulf accords, the Islamic accords? Oh brothers in blood and language, Arabism and Islamism, rise up with us. Kuwait is appealing to you.”

On Iraqi radio, Saddam Hussein was threatening to turn Kuwait into a graveyard if there were any foreign intervention.

The next morning we woke early to the sound of renewed fighting and found our area swarming with soldiers. Some went to houses asking for food and water, others broke in with guns aimed at point-blank range. Homes of Kuwaiti families away on summer holiday were looted. We decided it was time to leave the area.

Realising it would be dangerous to be identified as an American, I put on a hijab and abaya, and stuffed clothes into a bag. My husband loaded the car with food and called his family to tell them we were on our way.

When we reached the 5th Ring Road we saw the awful reality of the Iraqi war machine: tanks, rocket launchers, jeeps, ammunition trucks, and half-tracks lined the highway. And blocking the road every 100 meters were Iraqi troops bristling with weapons. From their red berets we recognised them as Iraq’s elite Republican guards.

My heart sank when the first group of soldiers ordered my husband out of the car. Finally, after they checked his ID and thoroughly searched the trunk of our car we were allowed to drive on. With more roadblocks and heavy traffic we continued at a snail’s pace. At long last, we reached my mother-in-law’s house near Kuwait City. The family had anxiously been awaiting our arrival.

The days passed slowly. It soon became evident that many of the Iraqi soldiers did not want to be in Kuwait and wanted nothing to do with the invasion of a friendly neighbor.

At the roadblocks, some soldiers apologized to my husband. One said his aunt was married to a Kuwaiti. “Do you think I wanted to come here by choice and fight my cousins?” he asked.

Despite widespread low morale among Iraqi forces, reports of atrocities became more and more frequent. Looting, rape, and torture were the order of the day. Looting was systematic and the soldiers worked like a plague of locusts, stripping the country bare.

As the Kuwaiti Resistance became more active, the Iraqi response became more brutal. A friend told us how soldiers had hunted down a 14-year old boy helping the Resistance in her area. When he ran into a neighbour’s house the soldiers chased him out and shot him in front of his family.

Increasing numbers of Kuwaitis were being taken from their homes or simply disappeared. Some were released after having been tortured, others were never heard from again.

A family friend told us of his 20-day ordeal under Iraqi detention. He had been picked up because soldiers had found a photocopied newsletter issued by the Resistance in his car. But even possession of a Kuwaiti flag or picture of the Amir were grounds enough for torture.

Our friend had been beaten and tortured with electric shock treatment. Every four days he was given two dates to eat and dirty water to drink. One night a soldier put a gun in his mouth, then removed it, telling him to speak his last words. The Kuwaiti captive recited a verse from the Quran and the soldier laughed and said, “Never mind, I’ll let you live today; maybe your turn to die will come tomorrow.”

I began having a recurring dream that left me in a cold sweat. In the dream I was walking down a road and on both sides of me were dead men hanging from trees, their faces contorted with expressions of agony. One night my husband came in, visibly shaken by what he had heard on Iraqi-controlled radio. “All foreigners must hand themselves in to the Iraqi authorities. The penalty for hiding a foreigner is death by hanging.” The knot of fear in my stomach grew tighter. I told no one of my dream.

The Iraqis began conducting house-to-house searches for foreigners and members of the Resistance. One morning the phone began ringing at dawn. Friends and neighbors were calling to warn us that Iraqi forces were headed our way. Although my presence in their home put my in-laws in terrible danger, they put on a brave face for my benefit.

Our plan for safeguarding my identity was that rather than hide I would wear hijab and abaya and hopefully blend in with the women of the family. We hoped the Iraqis would not notice my blue eyes. The doorbell rang and our hearts started pounding, but it was only the neighbor lady warning us that soldiers were nearby. It was lunchtime, and my husband instructed me to sit and eat with the women, with my back to the door, while he and his father sat outside. We sat in front of our plates of rice and lentils for what seemed like hours, until my husband came in and announced that for the time being, the coast was clear.

Unlike in other areas where soldiers methodically searched each home, the troops who had come to our area were in a hurry and searched only every other house. They skipped ours; others were not so fortunate.

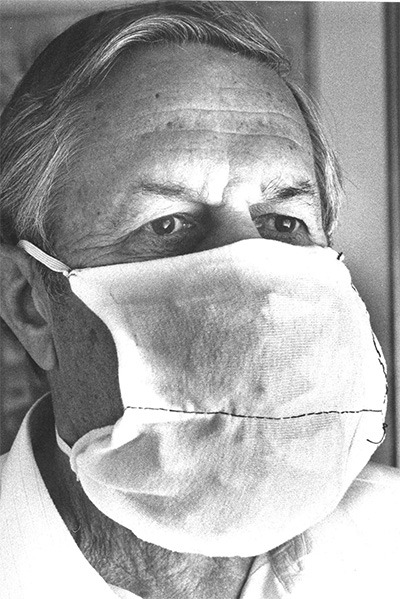

After Saddam Hussein threatened to use chemical weapons in Kuwait, the Resistance distributed information on how to deal with a poison gas attack, including instructions on how to make homemade gas masks. The method involves breaking natural wood charcoal into pea-sized pieces and frying them for thirty minutes. After cooling, the charcoal is sewn into cotton masks. It took me nearly two weeks to make fourteen masks for all the family members and house helpers.

Although civilians in Kuwait are entirely at the mercy of the occupying forces, there is an amazing strength and resolve among the population. One night this was dramatically demonstrated, and this is forever burned in my memory.

It was midnight on the one-month anniversary of the Iraqi invasion. Following a call for civil disobedience by the Resistance, families went on their rooftops and began shouting “Allahu akbar.” Suddenly, all over Kuwait, you could hear the voices of men, women, and children shouting in unison.

Iraqi soldiers, caught completely off guard, were terrified and started firing into the air. Tracer bullets streaked

the sky. In one area, to escape the haunting sound of the voices, soldiers got into their tanks and drove off into the desert. In another suburb, they locked themselves into the police station. The calling continued for nearly two hours. It was one night the Iraqis were afraid rather than us.

Nearly six weeks after the invasion I received a call from the American embassy telling me my children and I were scheduled to be on the next evacuation flight out of Kuwait. Saying goodbye to my husband and his family the morning of our departure was the hardest thing I have ever had to do, but my husband stressed that knowing the children and I would be safe would be an enormous load off his mind.

At the meeting point near the airport we were told to board a dirty old bus parked in the sun. It had no air-conditioning and the temperature was well over 40C. We were soon drenched in sweat. Babies and small children turned red from the heat and cried miserably.

Two hours later the Iraqi authorities gave us permission to make the ten-minute drive to the airport. We waited another hour before boarding an Iraqi Airways plane. The flight from Kuwait to Baghdad was less than an hour. We were greeted by swarms of reporters and camera crews but felt it was dangerous to be interviewed.

After filling out paperwork the long wait for our exit visas began. Iraqi immigration officers insisted that the children of Kuwaiti fathers were now officially Iraqis and therefore did not have the right to leave. They were also reluctant to accept travel documents that had been issued by the American Embassy in Kuwait to those who did not have passports.

Canadian embassy officials asked CNN to film the waiting women and children, so if we were taken into custody by the Iraqis, our presence would be documented. That was how my family in the US came to know my boys and I had left Kuwait and were in Baghdad.

After a tense five-hour standoff we were allowed to board another Iraqi Airways plane bound for London. At Gatwick Airport, Red Cross personnel wrapped us in warm blankets and carried our heavy handbags and exhausted children to a comfortable room where we could rest and make phone calls to our families.

We were finally safe, but our thoughts were with those we had left behind. Feeling isolated and forgotten, they live in a bizarre world of fear and uncertainty, where every day seems like an eternity.

As the world waits, the nightmare in Kuwait continues.

This article was published in a California magazine in January 1991 and was part of an information campaign I conducted with the Kuwait American Friendship Council. Kuwait was liberated on 26 February, 1991.

– Photographs by

Claudia Farkas Al Rashoud