By Qais A. Aljoan

Advisory Board member,

Reconnaissance Research

Special to The Times Kuwait

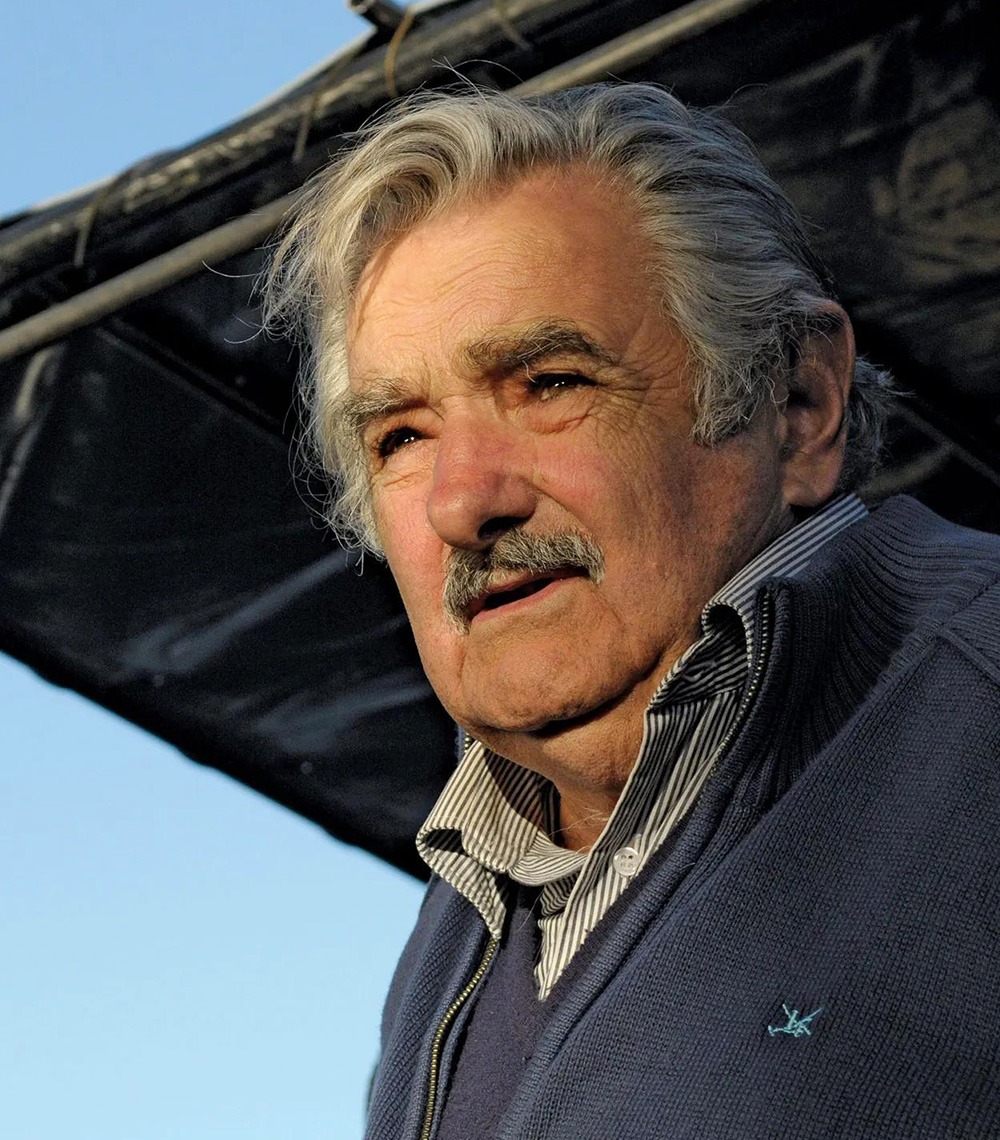

In an age when public office too often amplifies vanity, the life of José Mujica offers a rare counter example. From his early days as a militant, imprisoned and tortured under Uruguay’s military regime, to his ascent as a president known for refusing luxury and rejecting vengeance, Mujica lived a paradox—and a principle. His recent passing has stirred reflections far beyond Latin America, especially among those who still believe that politics can be a form of moral labor.

Mujica never denied his past. Nor did he mythologize it. Instead, he transformed it—not by erasing it, but by reinterpreting it through modesty and coherence. He chose to live in a humble rural home, drove a 1987 Volkswagen Beetle, and donated most of his salary. When asked about this simplicity, he answered, “I am not poor. Poor are those who need too much.” For Mujica, wealth lay in time—the most irreplaceable human asset. “You don’t buy things with money,” he said, “you buy them with the time of your life.”

There is something uncannily familiar in this ethical stance. One thinks of figures such as Umar ibn al-Khatāb or Alī ibn Abī Tālib—rulers who feared the seductions of power and insisted that leadership must reflect the lives of the people. Mujica’s rejection of personal vengeance, even against those who had tortured him, also recalls a prophetic ethic: justice without hatred, memory without vendetta.

I do not know why the news of his passing struck something so deep. Perhaps it is because, for those of us raised in the shadow of the pan-Arab moment—when Ahmad Shawqi’s verses were still etched into the classroom walls—Mujica awakened an old ethical instinct. “I will bear my soul in the palm of my hand,” Shawqi wrote, “and cast it into the abyss of death—either a life that delights my friends, or a death that enrages my enemies.”

Mujica did not speak our language, but he lived a truth that would not have felt foreign in that world—a world where simplicity, courage, and coherence once mattered more than strategy.

In a region like ours, where forgiveness is too often seen as weakness, Mujica’s restraint feels radical. And at a time when political legitimacy is frequently rooted in the logic of force, his life poses another question: might authenticity and humility still hold political power?

That question resonates more sharply today as the international stage shifts. Syria—long trapped in devastation—has witnessed an unexpected transition. A new leadership has emerged, sanctions have been softened, and figures once labeled as threats are now being shyly welcomed into the periphery of international diplomacy—signs of a possible reintegration, though the symbolic gestures that often define reconciliation have not yet occurred.

History is often stingy with second chances. Yet sometimes, from the margins of defeat or disgrace, a figure rises—not to erase the past, but to carry its weight differently. Could it be that, amid Syria’s long night, the soil is being turned for a quieter kind of leadership? Not one that dazzles with slogans or strength, but one that, in the spirit of Mujica’s ethos, might disturb us with its humility—and its refusal to hate.

In the end, Mujica asked not to be remembered. “Don’t remember me,” he said. “Remember the ideas.” Because what matters is not the origin of the leader, but the destiny they chart for their people—and the price they are willing to pay to live as they speak.