A European Explorer’s Forgotten Tale

Barklay Raunkiaer's desert trip, one of the best accounts of Arabian Travel

On 24th February, 1912, the day after his twenty-third birthday, Danish explorer Barclay Raunkiaer left Kuwait on a perilous desert journey by camel caravan. His goal was to find a base for a Danish expedition into the great southern desert of Arabia, then quite unknown to the Western world.

By Claudia Farkas Al Rashoud

Special to The Times Kuwait

On 24th February, 1912, the day after his twenty-third birthday, Danish explorer Barclay Raunkiaer left Kuwait on a perilous desert journey by camel caravan. His goal was to find a base for a Danish expedition into the great southern desert of Arabia, then quite unknown to the Western world.

For three weeks Raunkiaer had been a guest of the Amir of Kuwait, Shaikh Mubarak Al Sabah, lodging in the Sief Palace while preparing for his trek across largely unmapped desert to Riyadh, Buraidah, Hofuf, and ultimately Bahrain. After bidding farewell to his generous host, Raunkiaer’s caravan made its way out of Kuwait town, through streets so narrow that sometimes the camel packs scraped both sides of the walls.

During the long journey, the men endured incredible physical hardship. Raunkiaer had become seriously ill with fever in Kuwait. By the time he reached Riyadh he was barely able to walk, yet still managed to ride, clinging tenaciously to the back of his camel. The fever kept recurring throughout the journey, but despite his weak condition his powers of observation were keen. After his return to Denmark he wrote a detailed account of his trip titled “Through Wahhabiland On Camelback” published in Copenhagen in 1913.

Sadly, Raunkiaer never regained his health and succumbed to tuberculosis just two years later, at the age of 25. In 1916, Raunkiaer’s manuscript was translated from Danish into English and published by Great Britain’s Arab Bureau in Cairo. T.E. Lawrence, then affiliated with the Arab Bureau, praised it as one of the best accounts of Arabian travel. But with just one hundred copies printed, it would not have been read by many had it not been discovered by Gerald de Gaury who had it republished in 1968.

Sadly, Raunkiaer never regained his health and succumbed to tuberculosis just two years later, at the age of 25. In 1916, Raunkiaer’s manuscript was translated from Danish into English and published by Great Britain’s Arab Bureau in Cairo. T.E. Lawrence, then affiliated with the Arab Bureau, praised it as one of the best accounts of Arabian travel. But with just one hundred copies printed, it would not have been read by many had it not been discovered by Gerald de Gaury who had it republished in 1968.

De Gaury is himself a fascinating character. A highly-decorated military man and author of many books and articles on Arabia, he served as British Political Agent to Kuwait from 1936-39, directly succeeding Colonel Harold Dickson. Such a brave and adventurous man as de Gaury warrants much further description, but his story will be told in another article. For now, let’s return to Barclay Raunkiaer and his vivid portrayal of Kuwait in 1912.

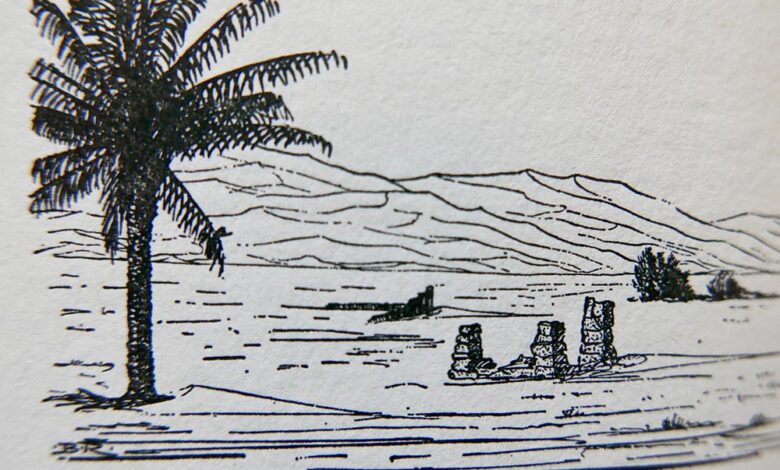

By the time Raunkiaer reached Kuwait he had already undergone an arduous overland journey from Copenhagen to Baghdad, sailed on a Tigris paddle steamer to Basra, and travelled south on horseback the rest of the way. The first settlement he came to in Kuwait was Jahra, which he described as “a village in flat, open surroundings with about five hundred inhabitants. North of the houses are a few fields…and a couple of date plantations, the number of palms not exceeding a hundred.”

The caravan stopped to water the camels and horses and take a midday rest in the shade of Jahra’s Red Fort. Upon leaving, Raunkiaer noted, “We constantly pass Arabs, either singly or in groups driving loaded donkeys—a sign that here is more public security than usually obtained in Arabia.”

Raunkiaer’s observation was correct. In those days, with most of the Arabian Peninsula in turmoil, Sheikh Mubarak’s strong rule of law made Kuwait an oasis of stability. In the desert outside Kuwaiti territory, Raunkiaer once nearly lost his life at the hands of hostile tribesmen but was spared when they learned he was traveling under the protection of Sheikh Mubarak.

Heading south, the approach to Kuwait town on weary horses plagued by flies, had its own austere beauty. “On we go, slowly and limpingly through the grey-green country. Not a breath of wind is astir. Eastwards stretches the Kuweit bay, glittering like a sheet of glass and on the far side of it lies Kuweit, a long low line of yellow dots,” wrote Raunkiaer. “Hour after hour passes without our seeming to come any nearer to the town; a beautiful sunset left all the western sky aglow, but it was soon quenched by rapidly falling darkness and still we have not reached Kuweit.”

Raunkiaer’s mindset of a punctual European who didn’t want to waste time, sometimes put him at odds with his travel companions. A hint of that can be perceived in his following remarks, “Already, at three o’clock in the afternoon, I had enquired of one of my Arabs how far it was to Kuweit. ‘An hour’s ride’ he answered. Two hours later I repeated the question. ‘An hour’ was again the answer. When two hours on, I put the same question and got the same reply, I gave up further enquiry, profoundly distrusting the Arabs’ estimate of time.”

They finally arrived at “a fortress-like building eight to ten meters high and of such great extent that its full bulk could not be made out in the night. Into this otherwise seemingly inaccessible mass of clay a very narrow lane penetrates and at its mouth we call a halt, because our pack-horses would have wholly blocked the passage. The lane is immediately filled by armed men…Very deliberately they take my letters of recommendation to be conveyed to Mobarek.”

Raunkiaer drew much attention as he and his men were led past heavily-armed men into the labyrinth of the fort. Eventually his baggage was piled into a room with a carpet on the floor where he could rest. Raunkiaer had arrived at the Sief Palace. During his stay, Sheikh Mubarak’s trusted man, Mohammed, was put at his disposal and instructed to show him the town. Although Raunkiaer would have liked to set off without delay, it is during this sojourn that he provided the only detailed description of Kuwait during this time period by a Westerner.

Raunkiaer remarked that of all Arab coastal towns, Kuwait town was “the least disturbed by foreign civilization.” It extended just over two kilometers along the seafront and barely one kilometer inland. Along the busy seafront he saw boats drawn up on shore for repair along with piles of timber for shipbuilding. “Bales of goods lie stacked in disorderly piles, the sun shines from a perfectly cloudless sky and out on the bay move various boats, whose curving lateen sails gleam in the sunshine on the blue green sheet of water like little white wings,” he wrote.

Raunkiaer put the number of Kuwait’s sailing vessels at about five hundred, with the larger ships used for trading voyages down the Gulf and over to India and Africa, and the smaller craft for pearling. He calculated the number of men engaged in the pearling industry to be between ten to fifteen thousand.

Kuwait’s population was much too small to provide so many men, so crews were recruited from the central Arabian hinterland through Mesopotamia to Persia, he observed. “In the month of April when the season is approaching, large caravans of young men are prepared in the Nejd oases, and these arrive on the coast, after several weeks’ journey through dangerous and forbidding deserts, to engage in an industry itself by no means free of danger and far from their homes deep in the motherland.”

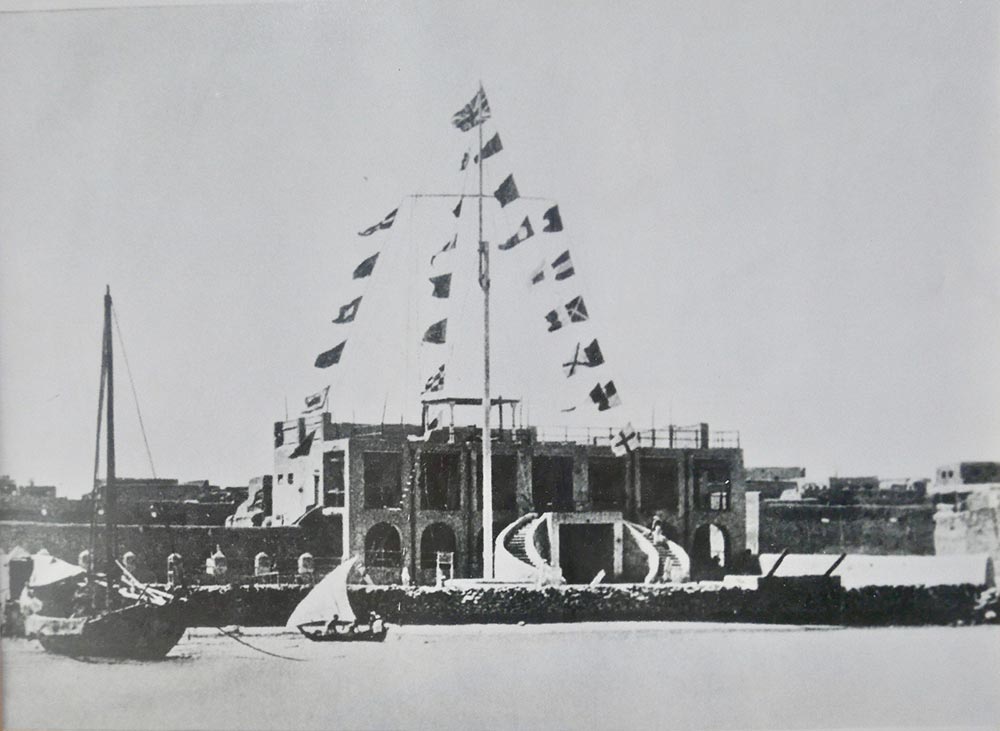

Raunkiaer described the British Political Agent’s house as a conspicuous building on the waterfront with the flag of Great Britain waving from a mast. A red lantern was hoisted on the mast at night to guide sailors. Known today as the Dickson House Cultural Centre, the blue and white house that served as the Political Agency was in those days situated directly on the water. Arabian Gulf Street was constructed on reclaimed land many years later.

Captain William Shakespear was British Political Agent at the time of Raunkiaer’s visit.

The young Dane was grateful to him for securing camels and a guide for his trip and providing him with letters of recommendation to other British officials in the Gulf. Raunkiaer also enjoyed many hours of hospitality at the Agency. The two men must have had a lot in common as Shakespear was also an avid explorer. He mapped uncharted areas of Northern Arabia and made the first official British contact with Ibn Saud, then the future king of Saudi Arabia. As fate would have it, both young men were to die the same year; Shakespear was killed in battle fighting alongside Ibn Saud’s forces in central Arabia in January 1915.

Raunkiaer spent a good deal of time in Kuwait’s cosmopolitan bazaar, noting that it attracted traders, merchants, and craftsmen from around the region. The market’s Safat Square was the arrival and departure point for camel caravans.

Other observations were about the modest style of local architecture, including Sheikh Mubarak’s audience hall in the bazaar, still in existence today. The mosques with their low, square minarets were barely taller than the roofs of the houses. The sandy lanes were conspicuously clean. The houses were usually only one story and made of sun-dried clay, with small windows facing the interior courtyard.

“The clay for houses comes from south and east of the town, where in consequence the ground is all uneven and full of holes. Clay is dug out anywhere a man happens to fancy or where his donkey has minded to stop. When the panniers on the donkey are full he is urged back to town, where the clay is soaked with water and kneaded with straw and twigs into a good cohesive mixture with which the houses’ walls are luted up.”

In summary Raunkiaer remarked, “Kuweit is emphatically a town of the desert and the sea, without any arable or garden ground whatever. Greenstuff and dates must be fetched from Fao and elsewhere and not a shady or beautiful growth is anywhere to be seen. It has not one single tree, if groups of stunted tamarisk be ruled out. To the mixture of seafaring men and nomads in its population, to both of whom digging and planting are uncongenial, it is owed that Kuweit is just a place of clay between steppe and sea.” Introducing Raunkiaer’s manuscript, Gerald de Gaury wrote that although the young adventurer didn’t fulfill his goal of establishing a base for an expedition into the south Arabian desert, his journey was still remarkable. His early death and the fact that de Gaury’s edition of his manuscript has been out of print for so long are probably why Raunkiaer is hardly known.

In 1968 de Gaury wrote, “Where Barclay Raunkiaer rode, no caravans pass today. Giant trucks loaded to capacity pound at high speed along motor roads….taking two days where he took a month or where he took two days, taking an hour. “Acceptance of a rafiq, or companion, from the tribes, and the payment of a toll as surety while in the dira of each one of them, is practice no longer. Desert lawlessness is cowed and there is peace.”

By Claudia Farkas Al Rashoud

Originally from California, Claudia Farkas Al Rashoud has enjoyed working in Kuwait since 1979, when she became the first professional female photojournalist for the Arab Times newspaper. She has written five books, with photographs, about Kuwait. Working as a freelance photographer for London-based picture libraries, her articles and photographs have appeared in many publications. She also serves as an ethnographic researcher and consultant. Claudia has also worked in the field of animal welfare in Kuwait for many years. All proceeds from her books and other work benefit Touch of Hope Kuwait, the largest animal shelter in the country. As a founding board member of the Kuwait Society for Animal Welfare and director of the education program, she gives presentations on animal welfare for schools, universities and community groups. She also speaks on other subjects including Kuwait’s history, heritage, natural history and environment, journalism and photography, and palliative care.

Please see @claudia_alrashoud @touch_of_hope_q8 @ksaw_q8