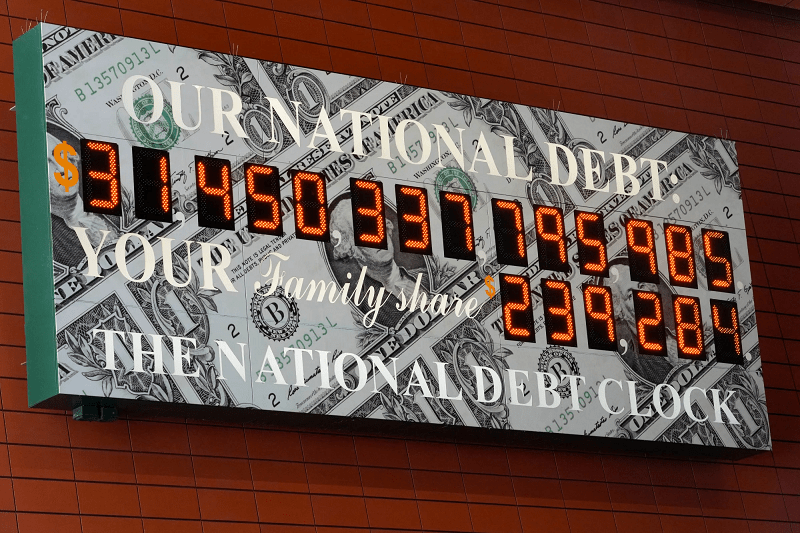

Since 1960, the United States has raised its debt ceiling 78 times – soon to be 79, if Congress approves the latest last-minute deal. On a wall in Manhattan, not far from Times Square, a billboard-size display has kept a running tally of the national debt amount.

Since its inauguration in 1989, the National Debt Clock has ticked inexorably higher, from $2.7 trillion to more than $31 trillion today. Never before has America or the world economy been so indebted. And since 2000, the stock of global debt has soared, from $87 trillion to over $300 trillion today – a rate nearly double the pace of world GDP growth.

Leaving aside the political theatrics, intrigue, and brinkmanship that nowadays accompany every increase in the US debt ceiling, can anything be done to stop, or even slow, the clock?

At the turn of the century, Switzerland devised a solution called a “debt brake,” which obliges the federal government to balance its budgets over the course of an economic cycle. In response to mounting public debt and repeating deficits in the 1990s, a group of Swiss economists and politicians began advocating for a constitutional amendment to limit government spending and borrowing. In 2001, the Swiss government proposed the debt brake, voters approved it overwhelmingly in a referendum, and it became a part of the country’s constitution.

The measure has yielded astonishing results. Since it was enacted, total government debt as a share of GDP has declined from 30% to 20%. Over the same period, debt has ballooned to unprecedented levels in Britain (186%), Japan (227%), the US (123%), and elsewhere.

Switzerland’s debt brake works because it has a simple and compelling goal: to limit the growth of public debt by preventing the government from spending money it doesn’t have. Moreover, because it is enshrined in the Swiss constitution, it has a high level of political legitimacy and is difficult to repeal or amend. And providing a clear benchmark against which progress can be measured makes elected officials’ more accountable to the citizens they represent and eliminates the temptation to run up debt to secure re-election while passing the burden of repayment to future generations.

At the same time, the debt brake is not a straitjacket. It includes automatic and countercyclical stabilizers, which allow for temporary deficits during periods of economic weakness, such as during the COVID-19 crisis, and encourages debt repayment during good times.

Today, Switzerland enjoys a AAA credit rating, which matters in a world of rising borrowing costs. At current levels of debt and interest rates, American taxpayers spend roughly 15 times more on interest payments than Swiss taxpayers. And while the Swiss thereby free up resources to invest in education, research, childcare, and other vital public goods and services, American taxpayers’ grandchildren will have to service the debt without ever having seen the benefits.

Nobody would deny the importance of the intergenerational social contract: the elderly pass their traditions and wisdom to the young, who bring fresh perspectives, ideas, and technological advances. But there must be a fair deal for everyone. The German word for debt, schuld, is also the word for ‘guilt’ — a kind of moral synonym reminding us to keep our end of the bargain.

Admittedly, the US Constitution is far more difficult to change than its Swiss counterpart. But the US founders regarded the accumulation of public debt as a matter of fundamental importance. They recognized that excessive debt could burden future generations, threaten economic stability, and compromise national independence. They knew that excessive debt led to the downfall of the Roman Empire, the French monarchy, the Dutch Republic, and the Spanish Empire. The recipe was always the same: costly wars and extravagant spending.

America’s founders, by contrast, believed in the importance of fiscal responsibility and advocated for limited government spending and the avoidance of excessive debt. Alexander Hamilton argued that the government should have the authority to borrow money under the strict condition that “the creation of debt should always be accompanied with the means of extinguishment.” And Thomas Jefferson believed that “to preserve [the people’s] independence, we must not let our rulers load us with perpetual debt.”

With that goal in mind, the US Constitution was designed with checks and balances to prevent abuses of power, including fiscal irresponsibility. While its framers assigned the power of the purse to the legislative branch, their intent was to ensure oversight and control of spending.

The US Constitution has been amended only 27 times since 1787, whereas the Swiss constitution is amended regularly. But a rigorous and challenging process implies greater legitimacy. This is what happened when 85% of Swiss citizens voted in favor of including a debt brake. American citizens deserve a chance to decide if they want something similar.

Author of Swiss Made: The Untold Story Behind Switzerland’s Success and Too Small to Fail: Why Some Small Nations Outperform Larger Ones and How They Are Reshaping the World.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2022.

www.project-syndicate.org